KONSTANTIN CHERNENKO, the general secretary of the Communist Party, died on the night of March 10th 1985 at the age of 73. As red flags trimmed with black ribbons went up in every city in the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev rushed to an emergency meeting of the Politburo in the Kremlin. That meeting put Mr Gorbachev in charge of the funeral committee—and thus, by extension, of the Communist Party and the country. Chernenko was of the generation that had risen through the ranks under Stalin. (And he was the third general secretary to die in less than three years, in what was memorably dubbed a “hearse race”.) After him, the party elders all felt that a younger, more dynamic leader was needed to rejuvenate the Soviet system and ensure its survival.

It was not until four the next morning that Mr Gorbachev returned to his dacha. As he and his wife walked the snow-covered paths of its garden, he summed up the mood of the elite and the country: “We just can’t go on living like this.” Nor did they. Mr Gorbachev gave individual livelihoods and well-being—the “human values”, as he put it—precedence over state or class interests, launching new policies ofglasnost (openness) andperestroika (restructuring), and bringing the cold war to a close.

The Soviet system could not keep going without deception and repression. Unwittingly and unwillingly, Mr Gorbachev brought about its end. What followed, however, was not the miraculous emergence of a “normal” country as many had hoped, but a decade of turbulence, economic decline, rising crime and social breakdown, and Mr Gorbachev got the blame. As he said years later, “It is my grandchildren’s generation who are benefiting fromperestroika. They are more confident, freer, they know that they must rely on themselves.”

Alexander Gabuev was born on the day Chernenko died. He is one of those “grandchildren”. Now 33, he is the chief China expert at the Moscow Carnegie Centre, a think-tank. Fluent in English, Mandarin and German, he criss-crosses the world briefing government officials. In his spare time, between playing tennis and drinking rum cocktails in a Moscow bar, he cultivates a network of young experts and policymakers to thrash out “actionable ideas” of how to reform the country when they come to power. “We need to be ready,” he says.

Olga Mostinskaya and Fedor Ovchinnikov are a few years older than Mr Gabuev. Ms Mostinskaya, 36, is a politician born into a family of diplomats. She spent ten years as an interpreter working directly for Vladimir Putin, Russia’s president, before resigning in 2014 “out of repugnance”. The war in Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea were only the last straw, she says. Three years later she was elected to a local council in Moscow on a pledge to “empower, inform and engage” her voters.

Mr Ovchinnikov, also 36, grew up in a family of journalists in Syktyvkar, near the Arctic Circle. He was a teenager when Mr Gorbachev, trying to raise money for his foundation, appeared in a Pizza Hut commercial with his ten-year-old granddaughter: “Because of him, we have opportunity!” a young man in the advert tells a disgruntled old-timer. A decade later, Mr Ovchinnikov used that opportunity to launch a pizza place in Syktyvkar. His firm, Dodo, now has 300 outlets in Russia, as well as one in Britain and two in America.

Regeneration

Belonging to a generation involves more than proximity of dates of birth. As Karl Mannheim, a German sociologist, wrote in 1928, a meaningful generation is also forged by the common experience of a trauma that becomes central to its identity. Contemporaries become a generation, he argued, only when “they are potentially capable of being sucked into the vortex of social change.”

Mr Gabuev, Ms Mostinskaya, Mr Ovchinnikov and other Russians are part of a new generation of Russian elite who share the European values declared by Mr Gorbachev around the time of their birth and are traumatised by their reversal 30 years later. A significant and vocal group, they are imbued with a sense of entitlement and have the potential and desire to complete Russia’s aborted transition to a “normal” country. Whether they get a chance to do so depends on many factors, including their determination and the resistance of the system embodied by Mr Putin’s rule.

The new generation define themselves by their difference from their “fathers” as well as some similarities with their “grandfathers”. Gorbachev’s grandchildren recognise in each other a dissatisfaction with the aggression, degradation and lies that underpin Mr Putin’s rule. He presides over the sort of power structure that Douglass North, an American political economist, has called the “natural state”. In this, rents are created by limiting access to economic and political resources, and the limits are enforced by “specialists in violence”. In Russia these are thesiloviki of the assorted security and police forces, serving the system as they did in Soviet times.

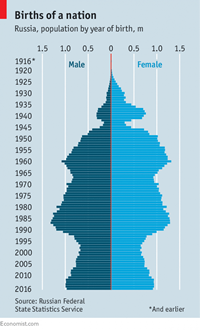

That system is not about to crumble. But the rise of a new generation—especially one which, through quirks of demography, is large (see chart)—matters in Russia. “Every new group coming to power has always declared a break with the previous one,” wrote Yuri Levada, a prominent Russian academic, “blaming it for every possible sin. A demonstrable rejection of predecessors has been the main way for leaders of a new generation to establish themselves in power, regardless of whether they carried on or changed the means and style of governance.”

Lacking strong civil institutions, Gorbachev’s grandchildren look to their peers for definition, for their place in society and, as Mannheim would have it, in history. But so do their opponents, the disenfranchised nationalists who are similarly dissatisfied with the corruption and cynicism of Mr Putin’s rule. The difference, at least for now, is that the nationalists lack leadership and resources and are overshadowed by the Kremlin’s own rhetoric.

Only one winner

The presidential election on March 18th showed, on the face of it, little prospect of any change. With television and the bureaucratic powers of the state at his beck and call, Mr Putin was re-elected with 77% of the vote. The result reflected the status quo and was hardly surprising. Many civil servants and factory workers were cajoled into voting by their bosses, and driven to the polls. Thanks to pre-election thuggery, Mr Putin faced no serious challenger. Boris Nemtsov, the most credible liberal politician of Mr Putin’s generation, was murdered three years ago, shot beside the wall of the Kremlin. Alexei Navalny, the most plausible candidate of the new generation, was barred from standing in December after the Kremlin engineered fraud charges against him.

“This is not an election,” said Igor Malashenko, who helped Boris Yeltsin keep the presidency in 1996. “It is a theatre performance directed by the Kremlin.” But he still thought it mattered. That is why he ran the campaign of Ksenia Sobchak, a 36-year-old socialite-turned-politician. Her father was the first democratically elected mayor of St Petersburg and once Mr Putin’s boss. She stood on the Kremlin’s sufferance. It used her as a spoiler for Mr Navalny, who is 41. But while the Kremlin used her, she hoped to use it to build a platform from which to move into real, as opposed to Potemkin politics. For both Ms Sobchak and Mr Navalny an appeal to a young generation is central to their politics.

Ms Sobchak’s strategy was the opposite of Mr Navalny’s. Once he had been barred from standing, he called for a boycott of the election to undermine its legitimacy. He accused Ms Sobchak of helping Mr Putin by taking part. Though blocked from standing, he managed to dominate the election agenda. Many young people are thought to have abstained, though it is hard to tell whether this was because of apathy or a rejection of Mr Putin.

As polling stations in Moscow closed, Ms Sobchak, who in the end got only 1.7% of votes, went to Mr Navalny’s headquarters blaming him for refusing to back her. He pushed her away, noting that her loss was a measure of his success. She looked deflated; Mr Navalny, off camera, uncorked the champagne. “We have created a new opposition in a place where it was impossible,” he said.

If the election was a ritual, it was still important. Giving Mr Putin another six years would “mark the arrival of the post-Putin era”, argued Ivan Krastev and Gleb Pavlovsky, two political analysts, in a recent paper for the European Council on Foreign Relations, a think-tank. Constitutionally Mr Putin cannot stand in 2024, and from now on political life will be dominated by the question of succession and expectation of his departure. His own survival and preservation of the system he now presides over will be his sole objective.

Mr Putin has seen crises of succession before—one brought him to power. As a youngKGB officer he served the ossified leaderships of Chernenko and Leonid Brezhnev. Their generation had grown old in power in part because it had won it young. Stalin’s purges meant that by 1940 around half the party elite was under the age of 40.

Who remembers the sixties?

The generation that followed identified themselves asshestidesiatniki—the men of the 1960s. Soviet victory in the second world war gave them confidence in their country. The 20th Congress of the Communist Party, at which Nikita Khrushchev denounced Stalin, gave them their political inspiration. Many of their spiritual leaders were children of old Bolsheviks killed in the purges. They had a sense of being both entitled and required to put the country back on the course of true socialism—this time with a human face. Those hopes were crushed when Soviet tanks rolled into Prague in 1968. They had to wait until 1985 for their chance.

The Brezhnev generation stayed long in power; the men of the 1960s did not. Mr Gorbachev was gone by 1991. Yeltsin, his contemporary and successor, was not part of that generation ideologically and surrounded himself with men who were 25-30 years his junior. The children of the 1960s men, the last Soviet generation, declared their fathers bankrupt both financially and intellectually. Socialism with a human face died with the Soviet economy.

The alternative was capitalism, which Soviet propaganda had portrayed as a cut-throat and cynical system in which cunning and ruthlessness mattered more than integrity or rules, and where money was the only measure of success. The new elite did not abandon that view. Those with power and connections acquired the material attributes of Western life. They could not buy its institutions, rules or norms—but they were not interested in trying.

Meanwhile millions of people in the first post-revolutionary decade of the 1990s felt disoriented, robbed of social status and savings. This was cynically and successfully exploited by Mr Putin. Yeltsin had promoted him as a man who, although of the next generation, would protect the wealth and safety of the elite. But Mr Putin consolidated his power by rejecting Yeltsin’s legacy and demonising the 1990s. His first symbolic gesture was the restoration of the Soviet anthem, which Yeltsin had abandoned. This was quickly followed by real changes, including suppression of freedom of speech and redistribution of assets and rents.

Mr Putin has become the patron of a cohort of young technocrats in order to manage, and survive, the next generational shift. He wants these young men (as they are for the most part) to provide some economic modernisation while not upsetting the system or provoking social unrest. And he wants their continued deference and loyalty as he moves from father figure to grandfather. Today six regional governors, two ministers and 20 deputy ministers are in their 30s. Yet, politically Mr Putin needs these technocrats to preserve a system in which entitlements, privileges and rents are allocated not according to law or merit but by access to resources and by position in the social hierarchy. This system of “conditional” property rights has allowed Mr Putin’s friends and cronies to put their children into positions of wealth and power.

The son of Nikolai Patrushev, the secretary of the National Security Council and former chief of theFSB, heads a state-owned bank. The son of Sergei Ivanov, another formerKGB officer and old friend of Mr Putin, is the head of Alrosa, a state-owned firm which mines more diamonds than any other in the world. The son of Mikhail Fradkov, a former prime minister and intelligence service chief, heads a private bank which is the staple of the military-industrial complex. Many children of Mr Putin’s friends and cronies hold senior positions in Gazprom, Russia’s gas monopoly, or own firms that depend on its contracts. All of them enjoy positions and wealth thanks largely to their family names.

Yet this also makes them vulnerable to political changes that come with generational shifts. Russian elites have endlessly tried to establish unconditional property rights for themselves. Andrei Zorin, a historian at Oxford University, sees this yearning for institutions that can guarantee both physical security and the transfer of wealth across the generations as one of the main reasons that Russian elites have sought to emulate Western Europe.

Those who oppose

For all the difference in their tactics, Mr Navalny and Ms Sobchak share a vision of Russia as a normal European country subject to the rule of law. As a populist who comes from outside the system, Mr Navalny appeals to people alienated by the elites. He demands retribution and a complete overhaul of government, with those now in power barred from office. Ms Sobchak, who is far closer to the beneficiaries of Mr Putin’s rule, promises a change without exposing the elite to reprisal. Justifying this halfway house, she says “Everything in this country belongs to these people. Billions of dollars, the army and security services, the largest companies. They can lose it only if there is a social explosion and even then they will probably fight to the last bullet. But Putin does not want to be a Qaddafi.”

This realism reflects the view that, even among the children of the elite, there is an appetite for change. Dmitry Gudkov, a 37-year-old opposition politician whose coalition won a majority in more than a dozen local councils in Moscow, is also the son of a formerKGB lieutenant-colonel, says: “The children [of the elite] are feeling uncomfortable in the shadow of their parents. They don’t want to be associated with all this obscurantism, self-isolation and anti-Westernism. They don’t want to risk their businesses now by speaking out in public, but they are constantly sending us signals that they are on our side.” Mr Gudkov and Ms Sobchak are now forming a party together.

The loyalists who have come of age under Mr Putin, and benefited from his patronage—the cadre from which he draws the technocrats whom he hopes will shore up the system—credit him with rebuilding the state. But they, too, see change ahead. As Mr Pavlovsky puts it, they “want to make [the system] inhabitable”. But so did Mr Gorbachev when he came to power.

This interest in making or managing change, rather than simply benefiting from it, is relatively recent. In the 2000s Gorbachev’s grandchildren seemed apolitical. Soaring incomes, the opening ofIKEA stores and a mushrooming of cafés, bars and nightclubs in Moscow were not taken as an achievement of the state, for which they should be grateful, but as a norm which they took for granted. They saw the end of the cold war not as a loss, but as part of becoming a normal country.

Mr Putin (and his circle) had a complex relationship with the West, coloured both by features of his generation and his service in theKGB. “As part of the last Soviet generation he longed for Western comforts and goods. As aKGB officer, he was instilled with an idea of the West as an enemy,” says Natalia Gevorkyan, Mr Putin’s biographer. The result was aressentiment mixture of jealousy and inferiority which fuelled anti-Americanism.

To Gorbachev’s grandchildren, by contrast, the West was just a place where they went. They did not crave its material attributes because they already had them. What they wanted were its institutions and rights. While older liberals lamented their lack of politics and public life, they were cultivating their urban space, with its parks, bike lanes and food courts. This shaped their expectations and sensibilities more than political statements. The presidency of Dmitry Medvedev, a place-holder installed by Mr Putin in 2008, fitted stylistically with this urban modernisation.

The new generation had no great enthusiasm for Mr Medvedev’s politics, but they liked the fact that he loved his iPad (Mr Putin prides himself on never using the internet). As rumours of Mr Putin’s return to the Kremlin began to swirl, though, Mr Medvedev started to become something more—a figurehead for a modernisation which he was not really enabling, but from which Mr Putin’s return would be a step back. When in September 2011 Mr Medvedev announced a pre-arranged job swap with Mr Putin, who had sat out one presidential term as prime minister, frustration boiled over.

Old style, new style

A rigged parliamentary election in 2011, which a few years earlier would have gone unnoticed, triggered protests in Moscow and other big cities; hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets. Mr Navalny galvanised the movement using social networks. The young, including the previously apolitical elite, joined in. Ms Sobchak, once known only as an it-girl and star of reality television, stood in front of a crowd and declared, “I am Ksenia Sobchak and I have much to lose.”

In anger, Mr Putin turned his back on the young and the educated, appealing instead to older members of the working class and public-sector workers and unleashing nationalist and traditionalist rhetoric that infringed on the urban elite’s style and private space. “It was my breaking point,” Ms Sobchak says now, “they started taking away what we already had.” Andrei Sinyavsky, a writer jailed for anti-Soviet propaganda, quipped after emigrating to France in the 1973 that his “differences with the Soviet regime were purely of a stylistic nature”. The new generation increasingly defines itself by such stylistic differences, rather than through any sort of political cohesiveness. But style in Russia often becomes politics.

Gorbachev’s grandchildren have never had to worry about being left penniless and that means they are less bothered about money. Success in the 1990s meant having a chauffeur, shopping in London and eating at $200-a-head restaurants. To be cool today is to use car-sharing, attend a public lecture about urbanism or make your own way around India. “I prefer cycling around Kaliningrad to going by car,” says Anton Alikhanov, the city’s 31-year-old governor. “And I don’t understand why investors want to put money into building another three floors of a house, instead of increasing the value of their properties by cultivating public space.”

Value judgments

Many care instead about what they can accomplish professionally rather than what they can get and about what they share, not what they own. They do not envy Mr Putin’s cronies who live behind high fences, fly on private jets and have built special rooms for their fur coats. They ridicule them.

They hate the propaganda of state television, which for a long time was one of the main instruments of social control. It now irritates people more than the stagnating economy, according to Lev Gudkov of the Levada Centre, a think-tank. They live online in a world of individual voices. They speak a direct language. Hence the success of Yuri Dud, whose YouTube interviews of people with something to say, be they politicians, actors or rappers, are watched by millions. These are neither pro- nor anti-Kremlin but are simply outside the system. There was a similar striving for sincerity in the early 1960s when a plain, living language seemed an antidote to Soviet bombast. It is another thing Mr Gorbachev’s grandchildren and the men of the sixties have in common.

Mr Gorbachev drew his support from a vast number of scientists and engineers who had time and skill but lacked prospects. Today, the demand for change is coming from an army of young entrepreneurs who want a system regulated by rules and open to competition. For people like Mr Ovchinnikov, business has become a form of activism. Openness is both his core business principle and selling point.

Mr Ovchinnikov turned Dodo’s growth into something resembling a reality television show through a blog called Sila Uma (Brainpower). Both investors and customers watched Dodo deliver both pizza and profits in real time. “We wanted to prove that you can be honest and transparent in Russia.” Within a few years Dodo, largely crowdfunded through the internet, employed 10,000 people. Mr Ovchinnikov and others like him treat transparency not as a risk, but as a way of protecting themselves from the system.

“There are two parallel countries,” Mr Ovchinnikov says. “There is a country of smart and energetic people who want to make it open and competitive. And there is another country of security servicemen who drive in blackSUVs extorting rents.” The two clashed when, earlier this year, Mr Ovchinnikov was accused of pushing drugs after the staff of one of his pizza joints in Moscow reported finding drugs in a lavatory that had, in fact, been planted by criminals with police protection apparently in order to extract a bribe or ruin his business. Mr Ovchinnikov gave his side of the raid through social media and the story went viral. It was picked up by Mr Navalny who mentioned it in one of his YouTube videos. A few weeks later the prosecutors backed off.

That will not always be the case. Part of North’s logic of the “natural state” is that when rents get scarce the role of violence goes up. Many young Russians see a job in the security services as the only social lift available. A recent survey found that more than 75% of people under the age of 30 find a security-service job attractive and 50% would like their children to have one. And which way the spooks turn will affect Russia’s future. ManyFSB officers are apparently in “suitcase” mood, ready to switch sides if necessary. But some are more ideological, and therefore more dangerous.

Last autumn, youngFSB officers in a unit called the “Service for the Protection of Constitutional Order and the Fight Against Terrorism” arrested several anarchists and left-wing anti-fascists, accused them of trying to “destabilise the political situation in the country” and subjected them to torture and humiliation. As one victim was told as he was tasered: “You must understand, anFSB officer always gets what he wants.” Social-media profiles of some of those officers revealed their ultra-nationalist views. None of them has been charged or dismissed.

The impunity that the security services have gained under Mr Putin has reversed Mr Gorbachev’s main principle: individual life and human values take precedence over the purposes of the state. Gorbachev’s grandchildren want those values back. “The current state system is not only incompetent. It is immoral,” says Mr Gabuev. “A state should be a service, not an idol.”

Vote for change

The young elite is resentful of pretence, simulation and cynicism—the staples of the current system. Instead they crave convictions and ideas. This was one reason why many Russians refused to cast a ballot on March 18th. Neither Mr Gabuev nor Mr Ovchinnikov saw any point in going to the polls. Ms Mostinskaya, by contrast, did. “Participation gives you a right to act in the future,” she says. Rather than backing one of the candidates, she spoiled her ballot paper by scribbling on the top: “One day, even if not now, all this will change.”

fecha |

Título |

23/09/2023| |

|

06/09/2022| |

|

17/09/2020| |

|

15/09/2020| |

|

18/08/2020| |

|

05/07/2020| |

|

01/06/2020| |

|

30/05/2020| |

|

15/05/2020| |

|

26/04/2020| |

|

14/04/2020| |

|

04/04/2020| |

|

24/03/2020| |

|

19/01/2020| |

|

23/08/2019| |

|

22/08/2019| |

|

20/08/2019| |

|

21/07/2019| |

|

04/02/2019| |

|

13/01/2019| |

|

26/12/2018| |

|

24/12/2018| |

|

04/10/2018| |

|

13/08/2018| |

|

12/08/2018| |

|

07/08/2018| |

|

03/08/2018| |

|

28/07/2018| |

|

25/07/2018| |

|

23/07/2018| |

|

23/07/2018| |

|

21/07/2018| |

|

01/07/2018| |

|

12/06/2018| |

|

26/04/2018| |

|

22/04/2018| |

|

10/04/2018| |

|

20/03/2018| |

|

04/03/2018| |

|

03/02/2018| |

|

11/12/2017| |

|

11/12/2017| |

|

11/12/2017| |

|

02/12/2017| |

|

17/11/2017| |

|

16/11/2017| |

|

07/11/2017| |

|

01/11/2017| |

|

28/10/2017| |

|

26/10/2017| |

|

05/10/2017| |

|

26/09/2017| |

|

09/09/2017| |

|

20/08/2017| |

|

19/08/2017| |

|

14/08/2017| |

|

01/08/2017| |

|

22/07/2017| |

|

20/07/2017| |

|

15/07/2017| |

|

09/07/2017| |

|

07/07/2017| |

|

12/06/2017| |

|

10/06/2017| |

|

13/05/2017| |

|

13/05/2017| |

|

30/04/2017| |

|

19/04/2017| |

|

18/04/2017| |

|

04/04/2017| |

|

28/03/2017| |

|

28/03/2017| |

|

17/03/2017| |

|

12/03/2017| |

|

05/03/2017| |

|

05/03/2017| |

|

24/02/2017| |

|

24/02/2017| |

|

22/02/2017| |

|

22/02/2017| |

|

20/02/2017| |

|

01/02/2017| |

|

16/01/2017| |

|

16/01/2017| |

|

15/01/2017| |

|

10/01/2017| |

|

01/01/2017| |

|

24/11/2016| |

|

20/11/2016| |

|

11/11/2016| |

|

24/10/2016| |

|

17/10/2016| |

|

15/10/2016| |

|

14/10/2016| |

|

14/10/2016| |

|

13/10/2016| |

|

10/10/2016| |

|

01/10/2016| |

|

14/09/2016| |

|

09/09/2016| |

|

04/09/2016| |

|

04/09/2016| |

|

17/08/2016| |

|

14/08/2016| |

|

14/08/2016| |

|

16/06/2016| |

|

11/06/2016| |

|

06/06/2016| |

|

06/06/2016| |

|

27/05/2016| |

|

07/05/2016| |

|

14/04/2016| |

|

14/04/2016| |

|

11/04/2016| |

|

11/04/2016| |

|

25/03/2016| |

|

18/03/2016| |

|

18/03/2016| |

|

18/03/2016| |

|

15/03/2016| |

|

15/03/2016| |

|

13/03/2016| |

|

08/02/2016| |

|

07/02/2016| |

|

24/01/2016| |

|

05/01/2016| |

|

04/01/2016| |

|

31/12/2015| |

|

16/12/2015| |

|

16/12/2015| |

|

11/12/2015| |

|

28/11/2015| |

|

21/11/2015| |

|

10/11/2015| |

|

07/11/2015| |

|

03/11/2015| |

|

31/10/2015| |

|

19/10/2015| |

|

19/10/2015| |

|

15/10/2015| |

|

28/09/2015| |

|

20/09/2015| |

|

18/09/2015| |

|

03/09/2015| |

|

31/08/2015| |

|

28/08/2015| |

|

21/08/2015| |

|

16/08/2015| |

|

08/08/2015| |

|

08/08/2015| |

|

30/07/2015| |

|

30/07/2015| |

|

22/07/2015| |

|

27/06/2015| |

|

27/06/2015| |

|

17/06/2015| |

|

09/06/2015| |

|

06/06/2015| |

|

03/06/2015| |

|

30/05/2015| |

|

30/05/2015| |

|

22/05/2015| |

|

21/05/2015| |

|

19/05/2015| |

|

06/05/2015| |

|

02/05/2015| |

|

03/04/2015| |

|

31/03/2015| |

|

29/03/2015| |

|

09/03/2015| |

|

04/03/2015| |

|

25/02/2015| |

|

19/02/2015| |

|

16/02/2015| |

|

16/02/2015| |

|

01/02/2015| |

|

01/02/2015| |

|

27/01/2015| |

|

27/01/2015| |

|

27/01/2015| |

|

23/01/2015| |

|

22/01/2015| |

|

13/01/2015| |

|

13/01/2015| |

|

02/01/2015| |

|

02/01/2015| |

|

22/12/2014| |

|

21/12/2014| |

|

21/12/2014| |

|

18/12/2014| |

|

14/12/2014| |

|

04/12/2014| |

|

01/12/2014| |

|

01/12/2014| |

|

28/11/2014| |

|

20/11/2014| |

|

20/11/2014| |

|

12/11/2014| |

|

01/11/2014| |

|

21/10/2014| |

|

19/10/2014| |

|

18/10/2014| |

|

14/10/2014| |

|

12/10/2014| |

|

12/10/2014| |

|

12/10/2014| |

|

10/10/2014| |

|

06/10/2014| |

|

06/10/2014| |

|

01/10/2014| |

|

29/09/2014| |

|

29/09/2014| |

|

19/09/2014| |

|

15/09/2014| |

|

09/09/2014| |

|

01/09/2014| |

|

26/08/2014| |

|

26/08/2014| |

|

19/08/2014| |

|

19/08/2014| |

|

08/08/2014| |

|

29/07/2014| |

|

29/07/2014| |

|

27/07/2014| |

|

27/07/2014| |

|

21/07/2014| |

|

21/07/2014| |

|

21/07/2014| |

|

03/07/2014| |

|

01/07/2014| |

|

23/06/2014| |

|

21/06/2014| |

|

18/06/2014| |

|

18/06/2014| |

|

18/06/2014| |

|

29/05/2014| |

|

21/05/2014| |

|

17/05/2014| |

|

09/05/2014| |

|

09/05/2014| |

|

09/05/2014| |

|

05/05/2014| |

|

27/04/2014| |

|

20/04/2014| |

|

20/04/2014| |

|

20/04/2014| |

|

11/04/2014| |

|

07/04/2014| |

|

31/03/2014| |

|

31/03/2014| |

|

25/03/2014| |

|

04/03/2014| |

|

27/02/2014| |

|

21/02/2014| |

|

17/02/2014| |

|

14/02/2014| |

|

04/02/2014| |

|

31/01/2014| |

|

31/01/2014| |

|

25/01/2014| |

|

16/01/2014| |

|

15/01/2014| |

|

15/01/2014| |

|

14/01/2014| |

|

02/01/2014| |

|

25/12/2013| |

|

19/12/2013| |

|

11/12/2013| |

|

11/12/2013| |

|

06/12/2013| |

|

03/12/2013| |

|

03/12/2013| |

|

27/11/2013| |

|

25/11/2013| |

|

20/11/2013| |

|

17/11/2013| |

|

11/11/2013| |

|

08/11/2013| |

|

06/11/2013| |

|

05/11/2013| |

|

28/10/2013| |

|

28/10/2013| |

|

28/10/2013| |

|

27/10/2013| |

|

21/10/2013| |

|

21/10/2013| |

|

21/10/2013| |

|

16/10/2013| |

|

10/10/2013| |

|

09/10/2013| |

|

09/10/2013| |

|

29/09/2013| |

|

21/09/2013| |

|

17/09/2013| |

|

17/09/2013| |

|

15/09/2013| |

|

15/09/2013| |

|

14/09/2013| |

|

03/09/2013| |

|

27/08/2013| |

|

27/08/2013| |

|

17/08/2013| |

|

12/08/2013| |

|

12/08/2013| |

|

12/08/2013| |

|

07/08/2013| |

|

29/07/2013| |

|

18/07/2013| |

|

18/07/2013| |

|

12/07/2013| |

|

12/07/2013| |

|

11/07/2013| |

|

07/07/2013| |

|

06/07/2013| |

|

29/06/2013| |

|

21/06/2013| |

|

21/06/2013| |

|

16/06/2013| |

|

16/06/2013| |

|

16/06/2013| |

|

12/06/2013| |

|

03/06/2013| |

|

03/06/2013| |

|

30/05/2013| |

|

30/05/2013| |

|

28/05/2013| |

|

28/05/2013| |

|

28/05/2013| |

|

23/05/2013| |

|

23/05/2013| |

|

20/05/2013| |

|

20/05/2013| |

|

16/05/2013| |

|

16/05/2013| |

|

10/05/2013| |

|

10/05/2013| |

|

06/05/2013| |

|

04/05/2013| |

|

23/04/2013| |

|

21/04/2013| |

|

21/04/2013| |

|

19/04/2013| |

|

14/04/2013| |

|

11/04/2013| |

|

08/04/2013| |

|

03/04/2013| |

|

31/03/2013| |

|

22/03/2013| |

|

21/03/2013| |

|

14/03/2013| |

|

14/03/2013| |

|

11/03/2013| |

|

11/03/2013| |

|

11/03/2013| |

|

03/03/2013| |

|

03/03/2013| |

|

03/03/2013| |

|

03/03/2013| |

|

03/03/2013| |

|

25/02/2013| |

|

25/02/2013| |

|

18/02/2013| |

|

18/02/2013| |

|

18/02/2013| |

|

14/02/2013| |

|

14/02/2013| |

|

11/02/2013| |

|

11/02/2013| |

|

11/02/2013| |

|

27/01/2013| |

|

25/01/2013| |

|

22/01/2013| |

|

22/01/2013| |

|

15/01/2013| |

|

13/01/2013| |

|

10/01/2013| |

|

10/01/2013| |

|

10/01/2013| |

|

09/01/2013| |

|

09/01/2013| |

|

30/12/2012| |

|

25/12/2012| |

|

25/12/2012| |

|

24/12/2012| |

|

24/12/2012| |

|

19/12/2012| |

|

18/12/2012| |

|

18/12/2012| |

|

12/12/2012| |

|

08/12/2012| |

|

06/12/2012| |

|

05/12/2012| |

|

04/12/2012| |

|

04/12/2012| |

|

27/11/2012| |

|

26/11/2012| |

|

24/11/2012| |

|

24/11/2012| |

|

24/11/2012| |

|

19/11/2012| |

|

18/11/2012| |

|

18/11/2012| |

|

18/11/2012| |

|

10/11/2012| |

|

09/11/2012| |

|

09/11/2012| |

|

09/11/2012| |

|

07/11/2012| |

|

07/11/2012| |

|

07/11/2012| |

|

07/11/2012| |

|

07/11/2012| |

|

07/11/2012| |

|

05/11/2012| |

|

02/11/2012| |

|

02/11/2012| |

|

01/11/2012| |

|

31/10/2012| |

|

31/10/2012| |

|

30/10/2012| |

|

30/10/2012| |

|

26/10/2012| |

|

26/10/2012| |

|

26/10/2012| |

|

26/10/2012| |

|

19/10/2012| |

|

19/10/2012| |

|

19/10/2012| |

|

19/10/2012| |

|

19/10/2012| |

|

29/09/2012| |

|

10/09/2012| |

|

10/09/2012| |

|

10/09/2012| |

|

10/09/2012| |

|

10/09/2012| |

|

09/09/2012| |

|

01/09/2012| |

|

01/09/2012| |

|

01/09/2012| |

|

30/08/2012| |

|

24/08/2012| |

|

22/08/2012| |

|

22/08/2012| |

|

22/08/2012| |

|

21/08/2012| |

|

15/08/2012| |

|

15/08/2012| |

|

15/08/2012| |

|

13/08/2012| |

|

13/08/2012| |

|

10/08/2012| |

|

09/08/2012| |

|

09/08/2012| |

|

07/08/2012| |

|

06/08/2012| |

|

06/08/2012| |

|

06/08/2012| |

|

06/08/2012| |

|

31/07/2012| |

|

31/07/2012| |

|

31/07/2012| |

|

31/07/2012| |

|

28/07/2012| |

|

28/07/2012| |

|

28/07/2012| |

|

28/07/2012| |

|

28/07/2012| |

|

28/07/2012| |

|

28/07/2012| |

|

28/07/2012| |

|

25/07/2012| |

|

25/07/2012| |

|

15/07/2012| |

|

15/07/2012| |

|

14/07/2012| |

|

10/07/2012| |

|

10/07/2012| |

|

09/07/2012| |

|

14/06/2012| |

|

14/06/2012| |

|

09/06/2012| |

|

09/06/2012| |

|

09/06/2012| |

|

08/06/2012| |

|

04/06/2012| |

|

04/06/2012| |

|

03/06/2012| |

|

03/06/2012| |

|

21/05/2012| |

|

20/05/2012| |

|

20/05/2012| |

|

06/05/2012| |

|

27/04/2012| |

|

13/04/2012| |

|

13/04/2012| |

|

13/04/2012| |

|

12/04/2012| |

|

12/04/2012| |

|

07/04/2012| |

|

07/04/2012| |

|

06/04/2012| |

|

06/04/2012| |

|

04/04/2012| |

|

01/04/2012| |

|

01/04/2012| |

|

01/04/2012| |

|

19/03/2012| |

|

19/03/2012| |

|

18/03/2012| |

|

18/03/2012| |

|

12/03/2012| |

|

12/03/2012| |

|

04/03/2012| |

|

04/03/2012| |

|

04/03/2012| |

|

04/03/2012| |

|

04/03/2012| |

|

04/03/2012| |

|

04/03/2012| |

|

04/03/2012| |

|

02/03/2012| |

|

02/03/2012| |

|

02/03/2012| |

|

25/02/2012| |

|

25/02/2012| |

|

25/02/2012| |

|

25/02/2012| |

|

25/02/2012| |

|

25/02/2012| |

|

05/11/2011| |

|

30/10/2011| |

|

30/10/2011| |

|

29/10/2011| |

|

21/10/2011| |

|

11/10/2011| |

|

11/10/2011| |

|

08/10/2011| |

|

04/10/2011| |

|

03/10/2011| |

|

03/10/2011| |

|

03/10/2011| |

|

01/10/2011| |

|

01/10/2011| |

|

25/09/2011| |

|

24/09/2011| |

|

23/09/2011| |

|

23/09/2011| |

|

23/09/2011| |

|

23/09/2011| |

|

23/09/2011| |

|

20/09/2011| |

|

17/09/2011| |

|

17/09/2011| |

|

16/09/2011| |

|

15/09/2011| |

|

11/09/2011| |

|

11/09/2011| |

|

07/09/2011| |

|

07/09/2011| |

|

04/09/2011| |

|

04/09/2011| |

|

04/09/2011| |

|

04/09/2011| |

|

02/09/2011| |

|

02/09/2011| |

|

02/09/2011| |

|

02/09/2011| |

|

27/08/2011| |

|

27/08/2011| |

|

27/08/2011| |

|

27/08/2011| |

|

26/08/2011| |

|

26/08/2011| |

|

26/08/2011| |

|

26/08/2011| |

|

25/08/2011| |

|

25/08/2011| |

|

23/08/2011| |

|

23/08/2011| |

|

16/08/2011| |

|

16/08/2011| |

|

16/08/2011| |

|

16/08/2011| |

|

11/08/2011| |

|

11/08/2011| |

|

11/08/2011| |

|

07/08/2011| |

|

04/08/2011| |

|

29/07/2011| |

|

28/07/2011| |

|

24/07/2011| |

|

24/07/2011| |

|

23/07/2011| |

|

23/07/2011| |

|

22/07/2011| |

|

21/07/2011| |

|

21/07/2011| |

|

17/07/2011| |

|

17/07/2011| |

|

15/07/2011| |

|

15/07/2011| |

|

15/07/2011| |

|

15/07/2011| |

|

13/07/2011| |

|

13/07/2011| |

|

13/07/2011| |

|

13/07/2011| |

|

29/06/2011| |

|

29/06/2011| |

|

19/06/2011| |

|

19/06/2011| |

|

19/06/2011| |

|

19/06/2011| |

|

18/06/2011| |

|

18/06/2011| |

|

18/06/2011| |

|

18/06/2011| |

|

17/06/2011| |

|

17/06/2011| |

|

14/06/2011| |

|

14/06/2011| |

|

13/06/2011| |

|

13/06/2011| |

|

13/06/2011| |

|

13/06/2011| |

|

05/06/2011| |

|

05/06/2011| |

|

03/06/2011| |

|

03/06/2011| |

|

03/06/2011| |

|

03/06/2011| |

|

01/06/2011| |

|

01/06/2011| |

|

01/06/2011| |

|

01/06/2011| |

|

01/06/2011| |

|

01/06/2011| |

|

01/06/2011| |

|

01/06/2011| |

|

29/05/2011| |

|

29/05/2011| |

|

29/05/2011| |

|

29/05/2011| |

|

29/05/2011| |

|

29/05/2011| |

|

23/05/2011| |

|

23/05/2011| |

|

22/05/2011| |

|

22/05/2011| |

|

22/05/2011| |

|

22/05/2011| |

|

22/05/2011| |

|

22/05/2011| |

|

21/05/2011| |

|

21/05/2011| |

|

21/05/2011| |

|

21/05/2011| |

|

16/05/2011| |

|

16/05/2011| |

|

13/05/2011| |

|

13/05/2011| |

|

06/05/2011| |

|

06/05/2011| |

|

04/05/2011| |

|

04/05/2011| |

|

04/05/2011| |

|

04/05/2011| |

|

02/05/2011| |

|

02/05/2011| |

|

02/05/2011| |

|

02/05/2011| |

|

01/05/2011| |

|

01/05/2011| |

|

01/05/2011| |

|

01/05/2011| |

|

01/05/2011| |

|

01/05/2011| |

|

26/04/2011| |

|

26/04/2011| |

|

26/04/2011| |

|

26/04/2011| |

|

26/04/2011| |

|

26/04/2011| |

|

21/04/2011| |

|

21/04/2011| |

|

21/04/2011| |

|

21/04/2011| |

|

20/04/2011| |

|

20/04/2011| |

|

20/04/2011| |

|

20/04/2011| |

|

20/04/2011| |

|

20/04/2011| |

|

15/04/2011| |

|

11/04/2011| |

|

11/04/2011| |

|

08/04/2011| |

|

03/04/2011| |

|

27/03/2011| |

|

27/03/2011| |

|

26/03/2011| |

|

26/03/2011| |

|

20/03/2011| |

|

20/03/2011| |

|

19/03/2011| |

|

19/03/2011| |

|

19/03/2011| |

|

13/03/2011| |

|

13/03/2011| |

|

12/03/2011| |

|

11/03/2011| |

|

11/03/2011| |

|

09/03/2011| |

|

07/03/2011| |

|

07/03/2011| |

|

05/03/2011| |

|

04/03/2011| |

|

04/03/2011| |

|

04/03/2011| |

|

18/02/2011| |

|

21/01/2011| |

|

21/01/2011| |

|

16/01/2011| |

|

16/01/2011| |

|

11/01/2011| |

|

08/01/2011| |

|

02/01/2011| |

|

02/01/2011| |

|

29/12/2010| |

|

29/12/2010| |

|

28/12/2010| |

|

26/12/2010| |

|

13/12/2010| |

|

13/12/2010| |

|

08/12/2010| |

|

02/12/2010| |

|

30/11/2010| |

|

30/11/2010| |

|

28/11/2010| |

|

26/11/2010| |

|

26/11/2010| |

|

24/11/2010| |

|

16/11/2010| |

|

16/11/2010| |

|

16/11/2010| |

|

09/11/2010| |

|

07/11/2010| |

|

31/10/2010| |

|

31/10/2010| |

|

31/10/2010| |

|

26/10/2010| |

|

25/10/2010| |

|

22/10/2010| |

|

18/10/2010| |

|

16/10/2010| |

|

16/10/2010| |

|

11/10/2010| |

|

10/10/2010| |

|

10/10/2010| |

|

09/10/2010| |

|

05/10/2010| |

|

28/09/2010| |

|

28/09/2010| |

|

24/09/2010| |

|

24/09/2010| |

|

22/09/2010| |

|

22/09/2010| |

|

15/09/2010| |

|

15/09/2010| |

|

15/09/2010| |

|

12/09/2010| |

|

12/09/2010| |

|

12/09/2010| |

|

12/09/2010| |

|

06/09/2010| |

|

06/09/2010| |

|

05/09/2010| |

|

05/09/2010| |

|

29/08/2010| |

|

29/08/2010| |

|

29/08/2010| |

|

29/08/2010| |

|

22/08/2010| |

|

22/08/2010| |

|

21/08/2010| |

|

21/08/2010| |

|

21/08/2010| |

|

21/08/2010| |

|

21/08/2010| |

|

21/08/2010| |

|

14/08/2010| |

|

13/08/2010| |

|

13/08/2010| |

|

07/08/2010| |

|

07/08/2010| |

|

12/07/2010| |

|

12/06/2010| |

|

12/06/2010| |

|

12/06/2010| |

|

24/05/2010| |

|

24/05/2010| |

|

11/05/2010| |

|

10/05/2010| |

|

09/05/2010| |

|

09/05/2010| |

|

09/05/2010| |

|

01/04/2010| |

|

01/04/2010| |

|

31/03/2010| |

|

31/03/2010| |

|

31/03/2010| |

|

28/03/2010| |

|

28/03/2010| |

|

28/03/2010| |

|

20/03/2010| |

|

12/03/2010| |

|

12/03/2010| |

|

12/03/2010| |

|

08/03/2010| |

|

07/03/2010| |

|

06/03/2010| |

|

05/03/2010| |

|

03/03/2010| |

|

03/03/2010| |

|

28/02/2010| |

|

21/02/2010| |

|

19/02/2010| |

|

14/02/2010| |

|

11/02/2010| |

|

11/02/2010| |

|

10/02/2010| |

|

08/02/2010| |

|

08/02/2010| |

|

08/02/2010| |

|

28/01/2010| |

|

25/01/2010| |

|

20/01/2010| |

|

20/01/2010| |

|

16/01/2010| |

|

16/01/2010| |

|

15/01/2010| |

|

15/01/2010| |

|

11/01/2010| |

|

11/01/2010| |

|

10/01/2010| |

|

07/01/2010| |

|

03/01/2010| |

|

03/01/2010| |

|

03/01/2010| |

|

17/12/2009| |

|

15/12/2009| |

|

15/12/2009| |

|

13/12/2009| |

|

13/12/2009| |

|

28/11/2009| |

|

28/11/2009| |

|

28/11/2009| |

|

28/11/2009| |

|

27/11/2009| |

|

27/11/2009| |

|

27/11/2009| |

|

27/11/2009| |

|

27/11/2009| |

|

27/11/2009| |

|

21/11/2009| |

|

21/11/2009| |

|

18/11/2009| |

|

18/11/2009| |

|

16/11/2009| |

|

16/11/2009| |

|

30/10/2009| |

|

30/10/2009| |

|

11/10/2009| |

|

10/10/2009| |

|

10/10/2009| |

|

07/10/2009| |

|

07/10/2009| |

|

04/10/2009| |

|

30/09/2009| |

|

30/09/2009| |

|

27/09/2009| |

|

27/09/2009| |

|

27/09/2009| |

|

22/09/2009| |

|

20/09/2009| |

|

18/09/2009| |

|

18/09/2009| |

|

18/09/2009| |

|

16/09/2009| |

|

16/09/2009| |

|

16/09/2009| |

|

08/09/2009| |

|

07/09/2009| |

|

06/09/2009| |

|

06/09/2009| |

|

05/09/2009| |

|

05/09/2009| |

|

26/08/2009| |

|

21/08/2009| |

|

19/08/2009| |

|

19/08/2009| |

|

15/08/2009| |

|

15/08/2009| |

|

15/08/2009| |

|

11/08/2009| |

|

11/08/2009| |

|

11/08/2009| |

|

11/08/2009| |

|

19/07/2009| |

|

19/07/2009| |

|

18/07/2009| |

|

18/07/2009| |

|

27/03/2009| |

|

22/03/2009| |

|

22/03/2009| |

|

27/01/2009| |

|

27/01/2009| |

|

27/01/2009| |

|

17/01/2009| |

|

17/01/2009| |

|

17/01/2009| |

|

17/01/2009| |

|

17/01/2009| |

|

17/01/2009| |

|

11/01/2009| |

|

06/12/2008| |

|

06/12/2008| |

|

06/12/2008| |

|

06/12/2008| |

|

23/11/2008| |

|

23/11/2008| |

|

16/11/2008| |

|

16/11/2008| |

|

04/11/2008| |

|

04/11/2008| |

|

03/11/2008| |

|

03/11/2008| |

|

24/10/2008| |

|

24/10/2008| |

|

24/10/2008| |

|

24/10/2008| |

|

15/09/2008| |

|

15/09/2008| |

|

15/09/2008| |

|

15/09/2008| |

|

15/09/2008| |

|

15/09/2008| |

|

06/09/2008| |

|

06/09/2008| |

|

05/09/2008| |

|

05/09/2008| |

|

05/09/2008| |

|

05/09/2008| |

|

01/09/2008| |

|

01/09/2008| |

|

01/09/2008| |

|

01/09/2008| |

|

22/08/2008| |

|

22/08/2008| |

|

17/08/2008| |

|

17/08/2008| |

|

16/08/2008| |

|

16/08/2008| |

|

28/07/2008| |

|

28/07/2008| |

|

28/07/2008| |

|

28/07/2008| |

|

28/07/2008| |

|

28/07/2008| |

|

19/07/2008| |

|

19/07/2008| |

|

24/05/2008| |

|

24/05/2008| |

|

03/05/2008| |

|

03/05/2008| |

|

29/04/2008| |

|

11/02/2008| |

|

05/01/2008| |

|

09/12/2007| |

|

18/11/2007| |

|

10/11/2007| |

|

10/11/2007| |

|

06/11/2007| |

|

06/11/2007| |

|

06/09/2007| |

|

26/08/2007| |

|

25/08/2007| |

|

11/07/2007| |

|

16/06/2007| |

|

16/06/2007| |

|

10/06/2007| |

|

10/06/2007| |

|

19/05/2007| |

|

19/05/2007| |

|

19/05/2007| |

|

19/05/2007| |

|

24/04/2007| |

|

24/04/2007| |

|

14/04/2007| |

|

14/04/2007| |

|

05/04/2007| |

|

05/04/2007| |

|

05/04/2007| |

|

28/02/2007| |

|

28/02/2007| |

|

05/02/2007| |

|

05/02/2007| |

|

04/02/2007| |

|

04/02/2007| |

|

04/02/2007| |

|

04/02/2007| |

|

04/02/2007| |

|

04/02/2007| |

|

29/01/2007| |

|

29/01/2007| |

|

29/01/2007| |

|

29/01/2007| |

|

11/01/2007| |

|

11/01/2007| |

|

11/01/2007| |

|

11/01/2007| |

|

27/12/2006| |

|

27/12/2006| |

|

27/12/2006| |

|

27/12/2006| |

|

27/12/2006| |

|

27/12/2006| |

|

20/12/2006| |

|

20/12/2006| |

|

17/11/2006| |

|

30/09/2006| |

|

28/07/2006| |

|

12/04/2006| |

|

12/04/2006| |

|

12/04/2006| |

|

06/03/2006| |

|

21/02/2006| |

|

17/02/2006| |

|

31/01/2006| |

|

10/01/2006| |

|

28/12/2005| |

|

31/10/2005| |

|

26/09/2005| |

|

29/08/2005| |

|

11/08/2005| |

|

08/08/2005| |

|

24/06/2005| |

|

24/06/2005| |

|

24/06/2005| |

|

03/04/2005| |

|

03/04/2005| |

|

03/04/2005| |

|

03/04/2005| |

|