The US government's declaration of war on the Cachiros drug trafficking gang has sent a message to Honduras' economic and political elites that no one is safe -- but will the strategy backfire?

On September 19, the US Treasury Department announced it was targeting the Rivera Maradiaga family, which forms the core of the group known in Honduras as the Cachiros. Following the announcement, Honduran authorities began seizing what the US says is between $500 million and $800 million in properties -- a sum that any drug trafficker would envy.

It was the most important anti-narcotics operation since 1988, when the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) illegally arrested and extracted (in what can only be considered an early extraordinary rendition) Juan Ramon Matta Ballesteros, who was wanted for participating in the murder of DEA agent Enrique Camarena in Mexico three years earlier.

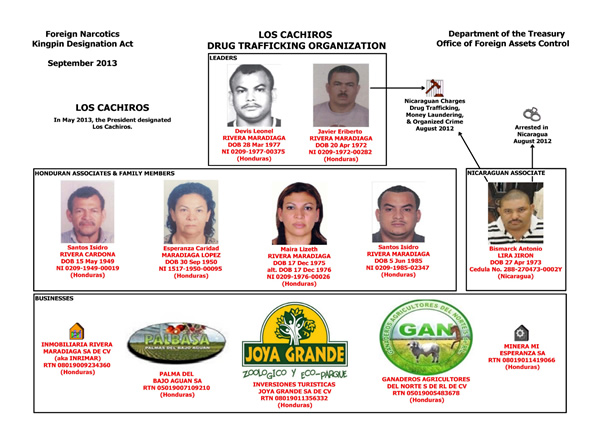

But the Cachiros (shown below in a Treasury Department organizational chart) have a humble heritage, and rose through the underworld first by stealing cattle from their neighbors, then by knocking off their boss in a Honduran jail in 2004. While formidable, violent and imposing, it's clear the Cachiros could not have accumulated half a billion in assets by trudging through manure.

Instead, the real target of this operation was almost certainly Honduras' political and economic classes, which have at best tolerated and at worst collaborated with groups like the Cachiros for years.

The day the seizures began, Lisa Kubiske, the US ambassador to Honduras, was speaking to representatives of the country's most powerful banks and financial institutions at an anti-money laundering conference. In what appeared to be something more than a coincidence, Kubiske sprinkled several hints that bigger names may follow in the multi-pronged investigation that involves the Treasury, the DEA and a few brave parts of the Honduran government.

"We all know that criminals are laundering money in Honduras," she said. "This is not a crime without victims. You all have seen the consequences of what is happening in this country."

These consequences include the highest murder rate in the world and a disintegrating sense of order in this nation of 8 million people.

"The institutions and the individuals who help or incite criminal organizations share the responsibility for the violence and the destruction that these groups have reaped on the people of Honduras," the ambassador continued. "Those who know they are helping launder money, for corrupt people or terrorists, should face long and costly legal procedures, sanctions and sentences. What I am saying is that if you are helping criminals, you are also criminals."

The ambassador went on to warn candidates that they too were being watched, and that more actions against more individuals and entities would follow.

"The financial institutions that are involved in criminal activities should be required to pay severe penalties and face the possibility that they will be prohibited from doing business," she said.

Other authorities, most notably the head of the Government's Banking and Insurance Commission, Vilma Morales, echoed the ambassador's message.

In contrast, Honduran President Porfirio Lobo has not uttered a word in public about what the Honduran authorities called "Operation Neptune," or about the Cachiros themselves. His silence can be interpreted in many ways, none of them good.

The president is in his last days, with elections for the next president taking place on November 24. And, like a "short-timer" nearing the end of his tour of duty, he is keeping his gun in his holster, trying to avoid getting into any battles.

As evidenced by the size of the Cachiros' holdings, he has presided over one of the largest underworld booms in recent memory, and his efforts to slow the spread of the scourge, and the violence associated with it, have failed miserably.

The United States has tried to right the ship, pouring nearly $65 million of its estimated $496 million in regional security assistance into Honduras in the last five years, according to the Congressional Research Service (pdf). It has privately admonished more than one official, and cajoled congress and the courts to pass an extradition law, among other important measures.

But the US intervention in Honduras may be too late and might provoke a violent backlash as it pins politicians between supporting its increasingly firm line and staying with that of the criminal interests.

The Honduran government, more than any other in the region, is tainted. To cite just one recent example, the current Attorney General, Oscar Fernando Chinchilla, was chosen during a late-night session that followed the resignation of several key extra-governmental committee members overseeing the process due to irregularities.

Chinchilla owes his job to his loyalty to the president of congress and presidential frontrunner Juan Orlando Hernandez, and a dubious bill that calls for "Special Development Networks." Several of his Supreme Court colleagues were illegally removed for calling the measure unconstitutional; he survived the purge, then was nominated for Attorney General.

The "Special Development Network" law is classic Honduras, cloaked in an argument for "development" but filled with ambiguous purposes and calls to remove all Honduran authorities, which may open more avenues for corruption and illegal drug trafficking. One of the areas to be designated is a Cachiro stronghold. Other areas also seem to coincide with important trafficking corridors.

With few trustworthy partners at the top, the impact of US victories is often limited when it runs up against the Honduran reality. This has been made clear by the hard-fought battle to get extradition on the books, as since the law passed only one person has been extradited, and he was a Guatemalan.

But the country's problems cannot be boiled down to simple corruption at the top. Much of the country lies outside of the national government's control, especially the municipalities in the western part of the country that, according to a recent United Nations report (pdf) on crime, are controlled by corrupt politicians, landowners and drug traffickers.

The country's economic model too is broken, and much of it is narco-generated. After the Cachiros' businesses were seized, for example, hundreds took to the streets in their stronghold of Tocoa, Colon, calling for the government to stop confiscating the businesses. Some said the criminal group employed between 5,000 and 8,000 people in that region alone.

The Hondurans know they are not innocent. But from their standpoint, the United States does not have the moral high ground either. Despite the violence, much of which is occurring around the fight for the local drug economy, Hondurans still see consumption as a US problem.

What's more, the US does not have a strong record of policing their own money launderers. The last two banks busted for money laundering in the US, Wakovia and HSBC, were fined small sums when compared to their annual earnings. What's more, the amounts involved in the schemes -- $400 billion in the Wakovia case alone -- dwarf the Honduran annual GDP of $18 billion, not to mention the Cachiros' holdings.

Standing between the US authorities calling for justice and the Hondurans cries of hypocrisy are the current presidential contenders. While they all pay lip service to the fight against organized crime, there are no good choices.

What may make or break them will be how they handle extradition. The threats against those working to introduce extradition as a tool to fight organized crime are already pouring in and several recent high profile murders have been linked to criminals' efforts to make sure none of them fall on a US court docket.

There are also votes and campaign money at stake. One marcher in Tocoa carried a sign warning one of the leading candidates that extradition of the Cachiros would put votes in jeopardy in the region. (There are no formal charges against the group's members in either the US or Honduras yet.)

The Hondurans also have a volatile history with regards to these types of legal intrusions. After DEA agents bundled up and shipped out Matta Ballesteros, who is still in a federal penitentiary in the US, angry Honduran protesters burned the US consulate in Tegucigalpa.

So far, there has been no backlash against the United States or the public in general. But some US embassy employees were put on high alert the day the seizures of the Cachiros' holdings began, and a Honduran court was closed briefly because of a bomb threat that turned out to be false.

The killings and the threats remind many of Colombia circa 1988 when Pablo Escobar and the so-called "extraditables" began kidnapping elites, detonating bombs in public spaces, and killing judges and policemen. That type of violent campaign seems unlikely, but the mere threat of it may be enough to keep the politicians closer to the criminals than to the US.

The research presented in this publication is, in part, the result of a project funded by Canada's International Development Research Centre.