The name BACRIM was created by the government of former President Alvaro Uribe in the aftermath of the demobilization of the AUC. Then-President Uribe was keen to draw a line in the sand, to avoid undermining the AUC peace process.

For this reason, any drug trafficking organizations post-2006 were not to be considered paramilitary groups, but rather, "criminal bands," (for the Spanish "bandas criminales" – BACRIM). Yet all but one of the BACRIM had their roots in the AUC. The exception that proved the rule was the Rastrojos, which emerged from the military wing of a faction of the Norte del Valle Cartel.

Today, the term BACRIM is used to describe a vast array of different criminal groups and enterprises -- essentially any criminal structure not linked to the Marxist rebels. In January 2011, former National Police Chief General Oscar Naranjo described the BACRIM as the principal threat to Colombia.[1] However, given the wide use of the term, it is necessary to define what constitutes a BACRIM, and how they fit into the criminal pecking order in Colombia.

The Third Generation of Colombian Drug Trafficking Organizations

The BACRIM are the third generation of Colombian drug trafficking organizations (DTOs). The first generation was made up of the Medellin and Cali Cartels. These cartels were vertically integrated, hierarchical organizations with a clearly marked command structure that was able to manage, in a centralized manner, all the different links in the drug chain, from drug crops to distribution in the United States.

The second generation of DTOs was made up of federations, comprised of "baby" cartels. These baby cartels tended to specialize in certain links in the drug chain. The Norte del Valle Cartel (NDVC), an association of drug traffickers whose roots lay in the Cali Cartel, was an example of this, as were the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC). Neither the NDVC nor the AUC had one clear boss. These were federations of drug traffickers and mafiosos that worked together, and, in many cases, ended up fighting each other.

The BACRIM thus constitute the third generation of Colombian drug trafficking syndicates, and are markedly different from their predecessors. The growing role of the Mexicans means the earning power of the BACRIM in the cocaine trade to the US is but a fraction of that of the first and second generation drug trafficking organizations. The BACRIM now deliver cocaine shipments destined for the US market to the Mexicans, usually in Central America (Honduras is one of the principal handover points). This means the BACRIM sell a kilo of cocaine in Honduras for around $12,000. The Mexicans then earn more than double that selling wholesale within the US and many times more if they get involved in distribution.

This has contributed to the diversification of the BACRIM's criminal portfolios. Whereas the first- and second-generation DTOs earned the lion's share of their money from the exportation of cocaine, the BACRIM perhaps gain half of their revenue from this. This means that their structures and capabilities are far different from those of their predecessors, which were designed solely for the production, transportation and sale of cocaine on international markets. The BACRIM are now engaged in a wide range of criminal activities: extortion, gold mining, micro-trafficking, gambling, contraband smuggling and human trafficking, among others.

The Narcos and the Enforcers

There is often a difference between the drug traffickers and the enforcers who regulate this illegal industry. Any market needs regulation, an authority to ensure that agreements are respected, debts are paid and deliveries made. In the markets for legal goods, it is the state that provides these services. In illegal markets, participants cannot turn to the state when agreements are broken, products stolen or payment refused. And criminal elements, by definition, tend not to be very trustworthy -- hence the high levels of violence associated with organized crime. In the days of the Medellin Cartel, Pablo Escobar served as judge, jury, and executioner in the cocaine world, regulating (and taxing) transactions.

With the fragmentation of the drug trade and the birth of the baby cartels and the second-generation DTOs after 1995, the scope for betrayal and conflict in the drug world became infinitely greater. After 1997, the AUC became the principal regulator of Colombia's drug trade. Heavily armed, with institutional links to the military and elements of the police force on the payroll, the paramilitaries became the "law" in Colombia's underworld, settling disputes. As the AUC expanded, many narcos joined the umbrella group, and many paramilitary commanders moved from serving as protection to working as drug traffickers in their own right. Thus the line between narco and enforcer became blurred.

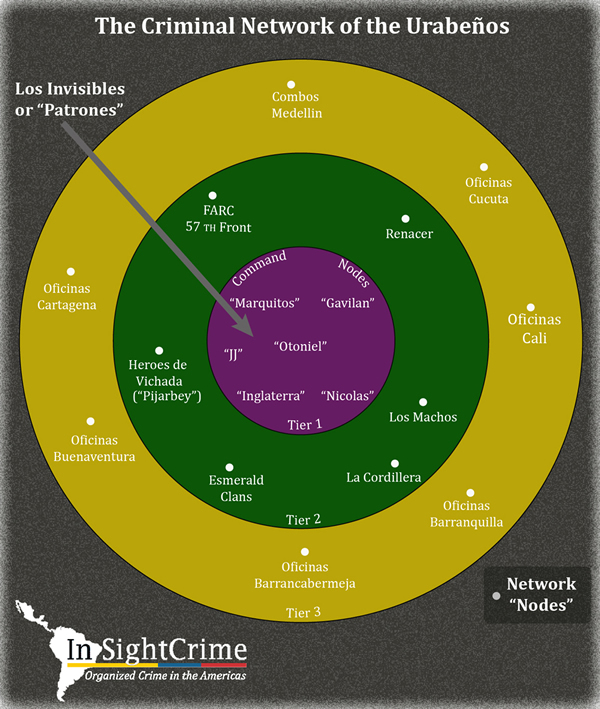

With today’s BACRIM, the difference between the narco and the enforcer has again become relevant. While many Urabeños leaders are narcos in their own right, this BACRIM group also provides services to other narcos who are not part of their core structure. There are drug traffickers in Medellin, often referred to as “Los Invisibles” by the police, who have direct links to the mighty Mexican cartels. They have access to coca and can subcontract laboratory work to get cocaine. However they do not have the power to move that cocaine from the laboratory to a departure point without risk of seizure. They do not have the power to prevent other criminals stealing their product en route. They do not have the power to ensure the transporters do not steal their shipments.

This is where the BACRIM fit in. The BACRIM are principally armed groups. They do have territorial control and they do control movement corridors across the country. They can secure departure points and they do have the ability to punish anybody that interferes with the flow of narcotics.

The BACRIM within Colombian Organized Crime

We have broken down Colombian organized crime into four different levels, with the BACRIM at the top. Using the criteria outlined here, it is clear that many groups described as BACRIM have been misidentified, and are really positioned, according to our analysis, further down the criminal food chain.

Type of criminal organization | Structure | Geography | Criminal Activities | Capacity for violence | Penetration/ corruption of state |

Pandilla | Mostly street gangs, with four members or more dedicated to criminal activity | Usually several city blocks, with the strongest perhaps controlling a neighborhood | Muggings, burglary, micro-extortion, local drug dealing | Most gang members will have access to some basic weaponry, but little training or planning capability | Limited, perhaps some local policemen who will take bribes to ignore criminal activity |

Combo/ banda | Could be made up of several pandillas or one or more groups specialized in a particular criminal activity. These groups can also supply services to more sophisticated criminal groups. | Often have city neighborhoods as strongholds, but criminal activity could be spread across a wider area. Usually based in one municipality. | Specialized criminal activities like car theft, but also extortion and local drug dealing. | Likely to have more discipline than the street gangs and access to better weaponry. | May have members who have served in the police or army and have some basic military skills. |

Oficina de cobro | This is a sophisticated criminal structure with different components and a wider range of criminal activities. It has its own armed wing capable of carrying out assassinations and armed actions. It also has a dedicated money laundering capability. Oficinas almost always have links to drug trafficking and provide services to transnational criminal organizations as well as BACRIM. | Oficinas can be rural as well as urban, and can call upon the services of affiliated pandillas and combos. An oficina at its most basic level will control a city district or rural area, while the most sophisticated control entire cities. They can have a presence in more than one municipality | Extortion, kidnappings, debt collection, administration of local justice, micro-trafficking, sicarios (hired assassin) services, prostitution, gambling, money laundering; can provide services related to some links in the drug trafficking chain (laboratories, access to drug crops etc) | An oficina will have its own group of sicarios. These will have basic weapons training and the ability to plan assassinations and armed actions. Usually have access to sophisticated weaponry, certainly assault rifles. Often have knowledge of explosives and can rig car bombs and Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs). | Can penetrate police and army units at the highest levels. Some oficinas have had local police chiefs on the payroll. Also can influence local politics and get members of the judiciary and judges on their side. |

BACRIM | This is a criminal structure capable of transnational criminal activity and able to provide a wide variety of services to drug traffickers. It consists of several different cells spread across a wide geographical area, with several armed components, personnel dedicated to paying off state functionaries, money laundering capabilities and the ability to carry out, or subcontract, a wide array of criminal activities. It is a criminal network rather than a hierarchical, integrated organization. | Usually has a presence in several departments. The weakest BACRIM have a regional presence; the strongest have a national reach and the ability to operate across the country. Many BACRIM also have cells in foreign countries capable of moving shipments and laundering money. | Drug trafficking, illegal gold mining, kidnapping, extortion, arms trafficking, providing services for all links of the drug chain in-country (purchase coca base, process cocaine, move shipments within country) and may also be able to engage in transnational transport of drug shipments. | Can call upon highly trained and well armed units, often made up of former members of the security forces. These units are able to carry out conventional military actions, have specialized weaponry and explosives skills. Some BACRIM can carry out these operations internationally.

| Can penetrate the state at a regional and even national level. Have the ability to corrupt high level officials in the security forces, local, regional and national government, the Attorney General's Office, the judiciary and customs. |

The BACRIM: A Criminal Network

Whereas the first generation cartels were vertically integrated and hierarchical organizations and the second generation were federations of baby cartels and paramilitary groups, the BACRIM are criminal networks that operate like franchises. They are made up of many different groups or “nodes,” all operating under the same umbrella, but often dedicated to different activities.

Criminal networks are far more fluid enterprises than the cartels or federations, with members coming and going depending on the services they offer and the criminal market that exists for those services. These networks are made up of different units or nodes that are interconnected for the purposes of business advancement and facilitation.[2] The current head of the Urabeños, Dario Antonio Usuga, alias "Otoniel," does not have direct control over even a tithe of the units that currently call themselves Urabeños. And only a tiny fraction of elements have any contact with Otoniel and his command node that sits at the heart of the Urabeños network.

The Urabeños network is a directed network, comprised of three tiers:

1. At the top is the command node headed by Otoniel and the senior military commanders of the organization, which form part of the "board of directors," or as they describe themselves using guerrilla terminology, the “Estado Mayor” (General Staff). Senior drug traffickers who are part of the Urabeños also sit at this level of the network. Past examples have included Henry de Jesus Lopez, alias "Mi Sangre," (captured in Argentina in October 2012) and Camilo Torres Martinez, alias "Fritanga," (captured in Colombia in July 2012). A current example is Carlos Alberto Moreno Tuberquia, alias "Nicolas."

2. At the second level are the Urabeños’ regional lieutenants, responsible for controlling certain territories and providing services that facilitate drug trafficking, including: providing access to drug crops, protecting laboratories, moving drug shipments and securing departure points. These regional lieutenants tend to be financially self-sufficient, running their own criminal enterprises in their territory, including extortion, micro-trafficking, gold mining, etc. But their primary role in the Urabeños franchise is to facilitate drug trafficking.

3. The third tier of the organization is the subcontracted labor. This includes a host of different criminal groups. The majority are oficinas de cobro, but some may be combos/bandas, which are hired to carry out specific tasks for the Urabeños. Those working at this level might use the name of the Urabeños to carry out their own criminal activities, and may be able to call upon the network for support if they get into trouble with the law or rival gangs. It is usually the regional command nodes that contract out this work, insulating the central command nodes from this criminal activity. The vast majority of Urabeños arrests come from this tier, and yet really they are not integral members of the BACRIM and have no connection with the board of directors. The Urabeños also provide services to other drug traffickers or criminal interests, and indeed use other criminal groups, like the FARC, where necessary, or profitable. An example of this is the 57th Front, which sits astride the border with Panama. The Urabeños deliver drug shipments to the guerrillas, who then move them into Panama, where they are received by other members of the Urabeños network.[3]

Outside of the core Urabeños network are different drug traffickers who use the services provided by the BACRIM. These are part of the wider drug trafficking network in Colombia. They are affiliated to the Urabeños, in the sense that they are either part of the franchise, or take advantage of the services provided.

The basic unit of the Urabeños network is the oficina de cobro, be it rural or urban. One example is the group Renacer. While described by the police as a BACRIM, Renacer was actually little more than a rural oficina de cobro that operated in Choco. It did not run its own international drug routes. Initially, Renacer worked with the Rastrojos; now, it is affiliated with the Urabeños.

The expansion of any BACRIM is based on its ability to persuade oficinas de cobro across Colombia (and increasingly abroad) to become affiliated with the franchise and provide services to the network. This model was initially pioneered by the Rastrojos, who after 2006 engaged in rapid expansion across the country, making agreements with local oficinas de cobro previously part of the AUC. These oficinas de cobro usually remain intact after affiliation, simply branding themselves according to the BACRIM franchise they are working with. This has been seen with oficinas de cobro in places like Barrancabermeja, which have changed hats with remarkable speed, starting life as part of the AUC, then becoming Aguilas Negras, later Rastrojos and today branding themselves as Urabeños.

While the line from paramilitary to BACRIM is easy to trace, and in many places the BACRIM are simply known as the same old "paracos" (common slang for paramilitaries), the truth is that the BACRIM are very different from their AUC predecessors. The AUC’s control of a region involved a highly visible presence with patrols carried out by uniformed troops carrying high caliber weapons, employing roadblocks and bases. The AUC had a professed anti-subversive ideology, and an ambitious political project that saw up to a third of Colombia's congress stacked with their allies. The BACRIM, on the other hand, lurk in the shadows, with civilian clothing and small arms. They are more reliant on intelligence networks than a visible military presence. Their commanders are faceless and hidden, with their names whispered throughout the communities they operate in. While they certainly backed candidates for the congressional elections in March 2014[4], they did this on an ad hoc basis, with different "nodes" seeking to get allies into power in their areas of influence. However, they did this more for the protection these politicians could provide to criminal operations than for any political program.

The BACRIM, unlike the AUC, do not have the military capability to take on the guerrillas, and they have no real desire to do so either. While the Urabeños still have some units of shock troops they can deploy, most of their members do not have the same military training that the paramilitaries once boasted. The military wing of the BACRIM is now the "sicarios," and while they are able to carry out sophisticated assassinations, they are not capable of military style attacks in a rural setting against the guerrillas. There have been few cases of serious BACRIM/guerrilla clashes, and those registered have been motivated by competition over criminal resources, such as coca crops.[5]

The BACRIM’s social role and integration into communities has also changed substantially compared with the AUC. Members of the AUC were commonly integrated into the business and social elites of many regions, who often invited them in to combat kidnapping and extortion by guerrillas. A number of prominent AUC commanders began as businessmen or members of the social elite.[6] The same is not true today.

There is a perception in certain regions that the BACRIM are a political force, since their violence often targets unionists, land restitution activists, and social movements that threaten business interests. The most likely reason for focusing their violence on these groups, however, is that the BACRIM operate as guns for hire. They are utilized by business and criminal interests to terrorize or eliminate opponents, but this does not mean these “political” actions are an inherent function of their existence.

Within the criminal network model, the BACRIM command often does not have total control over the self-financing regional nodes, and still less over the oficinas de cobro that are affiliated to the franchise and form the third tier of the structure. This means that the behavior of BACRIM units can vary drastically from region to region. In some areas, particularly the Urabeños heartland of Uraba and Cordoba, there is more continuity with the paramilitary era than in others.

References

[1] Semana, "Las bandas criminales son la principal amenaza para el país," January 25, 2011. http://www.semana.com/nacion/articulo/las-bandas-criminales-principal-amenaza-para-pais-general-naranjo/234587-3

[2] One of the best studies on the nature of these criminal networks can be found in Phil William's paper "Transnational Criminal Networks," RAND (2001).

[3] InSight Crime interview with Colombian police intelligence sources

[4] Caracol, "Elegidos 69 candidatos cuestionados por presuntos nexos con ilegales," March 10, 2014. http://www.caracol.com.co/noticias/actualidad/8203elegidos-69-candidatos-cuestionados-por-presuntos-nexos-con-ilegales/20140310/nota/2120176.aspx

[5] El Tiempo, “Bandas Criminales siembran minas en varias zonas del pais,” May 2013, http://www.eltiempo.com/justicia/campos-minados-por-bandas-criminales-en-el-el-nudo-de-paramillo_12825863-4

[6] See for example Rodrigo Tovar Pupo, alias “Jorge 40,” and Raul Emilio Hasbun, alias “Pedro Bonito”